2022-07-30

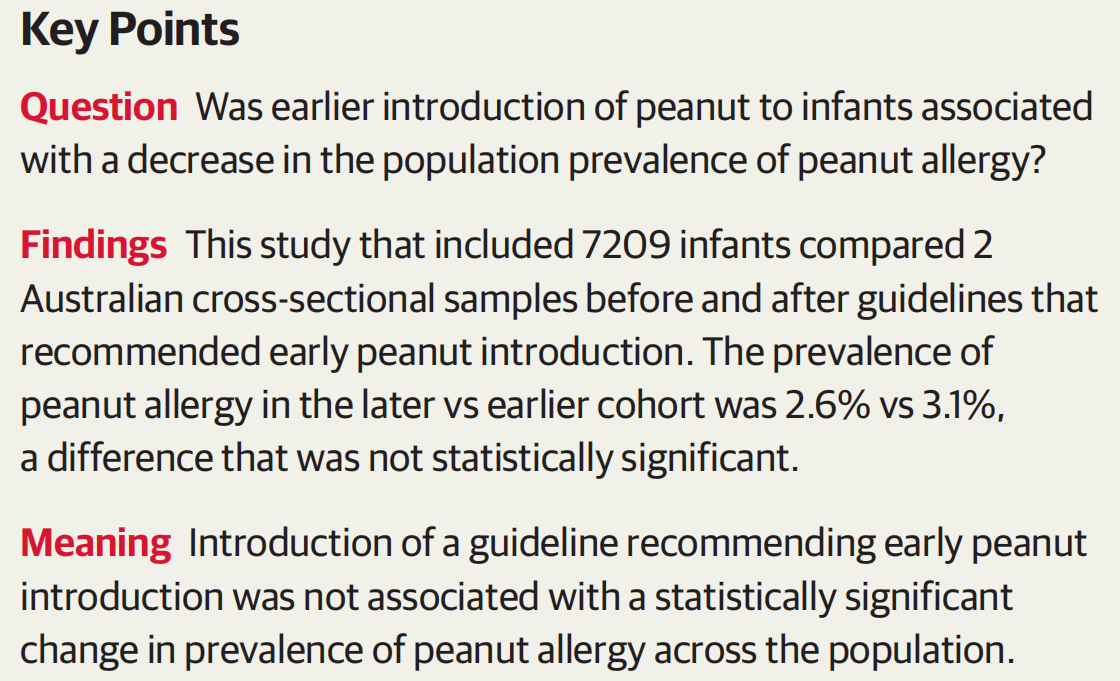

Peanut allergy is one of the most common childhood food allergies, and children rarely grow out of it. The only evidence-based prevention strategy currently available is timely introduction of peanut in the diet. Introduction of peanut by age 11 months was associated with a lower risk of peanut allergy (risk ratio, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.11-0.74]) in a metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials conducted in the UK. One was conducted in infants at high risk of developing peanut allergy.

花生过敏是最常见的儿童食物过敏之一,儿童很少能摆脱它。目前唯一可用的循证预防策略是在饮食中及时引入花生。一项在英国进行的随机临床试验的荟萃分析显示,在 11 个月大时引入花生与较低的花生过敏风险相关(风险比,0.29 [95% CI,0.11-0.74])。一项在婴儿中进行发生花生过敏的高风险。

These results led to infant feeding guidelines changing in 2016 in Australia to recommend introduction of peanut before age 12 months, although US guidelines initially restricted recommendations to high-risk infants only. This represented a major change from 1990s guidelines that recommended avoiding allergenic foods until age 1 to 3 years, leading to their widespread avoidance in infancy. By 2008, there was increasing evidence that delaying allergenic foods was associated with increased food allergy risk and avoidance was not recommended. Even so, most Australian parents from 2007 to 2011 still avoided feeding their infants peanut products before 1 year.8 There was an increase in infant feeding of peanut products in Australia after introduction of the 2016 guidelines. In 2 populationbased studies conducted in 2007 to 2011 and 2018 to 2019, introduction of peanut in the first year of life increased from 28% to 89%.

这些结果导致澳大利亚的婴儿喂养指南在 2016 年发生变化,建议在 12 个月大之前引入花生,尽管美国指南最初将建议仅限于高危婴儿。这代表了 1990 年代指南的重大变化,该指南建议在 1 至 3 岁之前避免过敏性食物,导致婴儿期普遍避免食用。到 2008 年,越来越多的证据表明延迟致敏食物与食物过敏风险增加有关,因此不建议避免食用。即便如此,从 2007 年到 2011 年,大多数澳大利亚父母仍然避免在 1 岁之前给婴儿喂食花生制品。8 在 2016 年指南出台后,澳大利亚婴儿喂食花生制品的情况有所增加。在 2007 年至 2011 年和 2018 年至 2019 年进行的两项基于人群的研究中,在生命的第一年引入花生的比例从 28% 增加到 89%。

It was not known to what extent early peanut introduction would reduce peanut allergy prevalence in the general population. The aim of the current study was to measure the change in prevalence of peanut allergy using these 2 cohorts, both in the general population and in predetermined subgroups of high-risk infants. It was hypothesized that a decrease in the prevalence of peanut allergy would be observed due to the shift toward early peanut introduction.

目前尚不清楚早期引入花生会在多大程度上降低普通人群的花生过敏患病率。本研究的目的是使用这 2 个队列,在普通人群和预先确定的高危婴儿亚组中测量花生过敏患病率的变化。据推测,由于向早期花生引入的转变,将观察到花生过敏患病率的下降。

Method

方法

Study Design

学习规划

Ethical approval for both studies was obtained from the Royal Children’s Hospital Research Ethics Committee (2007-2011:number 27047; 2018-2019: number 36160A). The 2018-2019 study was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (registration number ACTRN12618001990213) as an observational study. Parents or guardians provided written informed consent before participation.

两项研究均获得了皇家儿童医院研究伦理委员会的伦理批准(2007-2011:编号 27047;2018-2019:编号 36160A)。2018-2019 年的研究在澳大利亚新西兰临床试验注册中心(注册号 ACTRN12618001990213)注册为一项观察性研究。父母或监护人在参与前提供了书面知情同意书。

These 2 population-based studies used the same methodology, in Melbourne, Australia, to recruit participants 10 years apart. The baseline study, HealthNuts, was initially conceived as a cross-sectional study that recruited 5276 infants from September 2007 to August 2011. The 2018-2019 comparator study, EarlyNuts, was specifically designed to replicate the 2007-2011 study methodology and is the main sample of interest within these analyses. The study recruited from January 2018 to December 2019 (“Vanguard” study using the same protocol: November 2016 to December 2017).

这两项基于人群的研究在澳大利亚墨尔本使用相同的方法,以相隔 10 年的时间招募参与者。基线研究 HealthNuts 最初被设想为一项横断面研究,在 2007 年 9 月至 2011 年 8 月期间招募了 5276 名婴儿。2018-2019 年比较研究 EarlyNuts 专门设计用于复制 2007-2011 年的研究方法,是主要的研究方法。这些分析中感兴趣的样本。该研究从 2018 年 1 月至 2019 年 12 月招募(使用相同方案的“先锋”研究:2016 年 11 月至 2017 年 12 月)。

The studies have been described in detail. Briefly, both studies recruited infants from council-run immunization sessions at the time of their 12-month immunization visit. Eligible infants were aged between 11 and 15 months, regardless of exposure or allergy history. Infants underwent a skin prick test and open oral food challenges if the wheal size was 1 mm or larger (see eMethods in the Supplement). Parents completed questionnaires in the 15-minute wait time before the skin prick test results were read. Age of peanut introduction was evaluated with a researcher-administered questionnaire. Participants were excluded if the parent or guardian were unable to complete the questionnaires in English. Eligible parents who declined participation were asked to complete a nonparticipation survey (eBox in the Supplement).

已经详细描述了这些研究。简而言之,这两项研究都在 12 个月的免疫访问时从理事会运行的免疫会议中招募了婴儿。符合条件的婴儿年龄在 11 至 15 个月之间,无论是否有接触或过敏史。如果风团大小为 1 毫米或更大,则婴儿接受皮肤点刺试验和开放性口腔食物挑战(参见补充材料中的 eMethods)。家长在读取皮肤点刺测试结果之前的 15 分钟等待时间内完成问卷调查。花生引入的年龄通过研究人员管理的问卷进行评估。如果父母或监护人无法用英语完成问卷,则参与者被排除在外。拒绝参与的合格父母被要求完成一项不参与调查(补充中的 eBox)。

All electronic data were collected and managed using REDCap software hosted at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

所有电子数据均使用墨尔本默多克儿童研究所托管的 REDCap 软件收集和管理。

Exposures

曝光

The key measures are defined below, with additional definitions provided in the eMethods in the Supplement.

关键措施定义如下,补充定义的 eMethods 中提供了其他定义。

Early peanut introduction was defined as introduction of any peanut-containing product (eg, peanut butter) before 12 months (0-11 months) or as a categorical variable: 6 months or earlier, 7 to 9 months, and 10 to 11 months compared with greater than or equal to 12 months.

早期花生引入被定义为在 12 个月(0-11 个月)之前引入任何含花生的产品(例如,花生酱)或作为分类变量:6 个月或更早、7 至 9 个月和 10 至 11 个月比较 大于或等于 12 个月。

Early eczema (early-onset eczema) was defined as parentreported eczema diagnosis with onset in first 6 months of life that was managed with topical steroids (over-the-counter or prescribed).

早期湿疹(早发性湿疹)被定义为父母报告的湿疹诊断,在生命的前 6 个月内发病,并使用局部类固醇(非处方药或处方药)进行管理。

Infant ancestry was parent-reported maternal and paternal country of birth categorized into 10 country/regions: Australia, UK/Britain, Europe, Middle East, Africa, South America, North America, Oceania, South Asia, or East Asia (eMethods in the Supplement). Infant ancestry was grouped as Australian (both parents born in Australia), East Asian (1 parent born in East Asia 1 born in Australia or both born in East Asia), or other (all other combinations).

婴儿血统是父母报告的母亲和父亲出生国家,分为 10 个国家/地区:澳大利亚、英国/英国、欧洲、中东、非洲、南美、北美、大洋洲、南亚或东亚(补充材料中的 eMethods)。婴儿血统分为澳大利亚人(父母双方都出生在澳大利亚)、东亚人(父母一方出生在东亚、一名父母出生在澳大利亚或两者都出生在东亚)或其他(所有其他组合)。

Sex was defined as parent-reported sex of the infant.

性别定义为父母报告的婴儿性别。

Outcome

结果

The primary outcome was peanut allergy, defined as positive oral food challenge result or a clear history of recent reaction (within the past 2months) in infants with a skin prick test wheal of at least 1 mm (eMethods in the Supplement).

主要结果是花生过敏,定义为婴儿经口食物激发试验阳性或有明确的近期反应史(在过去 2 个月内),皮肤点刺试验风团至少为 1 毫米(补充材料中的 eMethods)。

Statistical Analysis

统计分析

Sample Size

样本量

The planned sample size of 2000 infants was estimated to have 81% power to detect a 40% relative decrease in peanut allergy prevalence in the study compared with the 2007-2011 study (3.1%), based on modeling showing an expected decrease of at least 40% when applying randomized clinical trial findings to the general population.

与2007-2011年的研究(3.1%)相比,该研究中2000名婴儿的计划样本量估计有81%的能力检测到花生过敏患病率相对下降40%,基于模型显示,当将随机临床试验结果应用于普通人群时,预期下降至少40%。

Descriptive Statistics

描述性统计

Each analysis was conducted as a complete case analysis, using all records with no missing data on the relevant variables. Participant characteristics were summarized throughout using percentages for binary variables and means for continuous variables, with the number of participants without missing data provided. To assess the representativeness of the recruited sample with respect to the eligible sample, characteristics between nonparticipants, partial participants, and complete participants were compared (eMethods in the Supplement).

每项分析都是作为一个完整的案例分析进行的,使用了所有记录,相关变量没有缺失数据。使用二进制变量的百分比和连续变量的平均值总结参与者特征,并提供无缺失数据的参与者数量。为了评估招募样本相对于合格样本的代表性,对非参与者、部分参与者和完全参与者之间的特征进行了比较(附录中的方法)。

Age of Peanut Introduction and Peanut Allergy

花生引进年龄与花生过敏

The association between age of peanut introduction and peanut allergy within studies was assessed using multivariable logistic regression models. Models were adjusted for risk factors of both peanut introduction and peanut allergy (socioeconomic status, infant ancestry, number of siblings, and family history of food allergy), as guided a priori using a directed acyclic graph (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) using DAGitty (version 3.0). Interactions between age at peanut introduction and the aforementioned risk factors were examined within each study using likelihood ratio testing. Stratified results were presented when P values were less than .05. A sensitivity analysis was performed adding early-onset eczema to the model.

使用多变量逻辑回归模型评估研究中花生引入年龄与花生过敏之间的关联。模型针对花生引入和花生过敏的风险因素(社会经济状况、婴儿血统、兄弟姐妹数量和食物过敏家族史)进行了调整,使用 DAGitty 使用有向无环图(补充材料中的图 1)进行先验指导 (版本 3.0)。在每项研究中使用似然比检验检查花生引入年龄与上述风险因素之间的相互作用。当 P 值小于 0.05 时,呈现分层结果。进行敏感性分析,将早发性湿疹添加到模型中。

Peanut Allergy Prevalence Estimates

花生过敏患病率估计

The 2018-2019 prevalence of peanut allergy was estimated as the observed percentage and compared with 2007- 2011 prevalence by calculating the absolute difference. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using inverse probability weighting to assess whether this estimate was affected by potential selection bias due to partial participation (eMethods in the Supplement). We then used direct regression standardization bootstrapped 1000 times to weight prevalence estimates of peanut allergy in the study to the population structure at baseline (2007-2011). Standardization models were adjusted for factors that changed substantially between the studies and that may alter the prevalence of peanut allergy (potential food allergy risk factors), as well as pet dog ownership and number of siblings because of strong evidence that these factors were associated with food allergy in 2007-2011, as guided by a directed acyclic graph (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). In addition, interaction terms between a covariate and study indicator (2018-2019 study or 2007-2011 study) were assessed using likelihood ratio testing and added into the model if P < .05. The primary multivariable logistic regression model used for standardization included study, infant ancestry, number of siblings, family history of food allergy, family history of hay fever, and dog ownership, plus an interaction term between study and family history of food allergy. Adjusted 2018-2019 prevalence was compared with 2007-2011 prevalence by calculating the absolute difference. Sensitivity analyses included stratifying the primary standardization analysis by age of peanut introduction categories (≤6 months, 7-9 months, 10-11 months, and ≥12 months). An additional post hoc analysis examined the prevalence of peanut allergy among those with and without early peanut introduction in the 2018-2019 study, both as the observed proportion and the standardized estimate.

将 2018-2019 年花生过敏的患病率估计为观察到的百分比,并通过计算绝对差异与 2007-2011 年的患病率进行比较。我们使用逆概率加权进行了敏感性分析,以评估该估计是否受到部分参与导致的潜在选择偏差的影响(补充中的 eMethods)。然后,我们使用直接回归标准化自举 1000 倍对研究中对基线人口结构(2007-2011 年)的花生过敏患病率估计进行加权。标准化模型针对研究之间发生重大变化的因素进行了调整,这些因素可能会改变花生过敏的患病率(潜在的食物过敏风险因素),以及宠物狗的拥有量和兄弟姐妹的数量,因为强有力的证据表明这些因素与食物有关2007-2011 年过敏,由有向无环图指导(补充中的图 2)。此外,使用似然比检验评估协变量和研究指标(2018-2019 研究或 2007-2011 研究)之间的交互作用项,如果 P < .05,则将其添加到模型中。用于标准化的主要多变量逻辑回归模型包括研究、婴儿血统、兄弟姐妹数量、食物过敏家族史、花粉热家族史和养狗,以及研究与食物过敏家族史之间的交互项。通过计算绝对差异,将调整后的 2018-2019 年患病率与 2007-2011 年患病率进行比较。敏感性分析包括按花生引入类别的年龄(≤6 个月、7-9 个月、10-11 个月和≥12 个月)对主要标准化分析进行分层。另一项事后分析检查了 2018-2019 年研究中早期花生引入和未引入花生过敏的患病率,包括观察到的比例和标准化估计值。

Subgroup Analyses

亚组分析

The standardization analysis described above was also stratified by prespecified high-risk subgroups of interest: presence or absence of early-onset eczema and infant ancestry (eMethods in the Supplement). Interactions between the study indicator (2018-2019 study or 2007-2011 study) and infant eczema and ancestry were assessed using likelihood ratio testing, but are presented as stratified irrespective of the P values to comply with predetermined analysis plans.

上述标准化分析还按预先指定的高风险感兴趣亚组进行分层:是否存在早发性湿疹和婴儿血统(补充中的 eMethods)。使用似然比检验评估研究指标(2018-2019 年研究或 2007-2011 年研究)与婴儿湿疹和祖先之间的相互作用,但无论 P 值如何,均以分层形式呈现,以符合预定的分析计划。

Significance level was decided a priori as P < .05. All analyses were conducted with the statistical software package Stata, release 17.0 (StataCorp).

显着性水平被预先确定为 P < .05。所有分析均使用统计软件包 Stata,版本 17.0 (StataCorp) 进行。

Results

结果

Study Population

研究人群

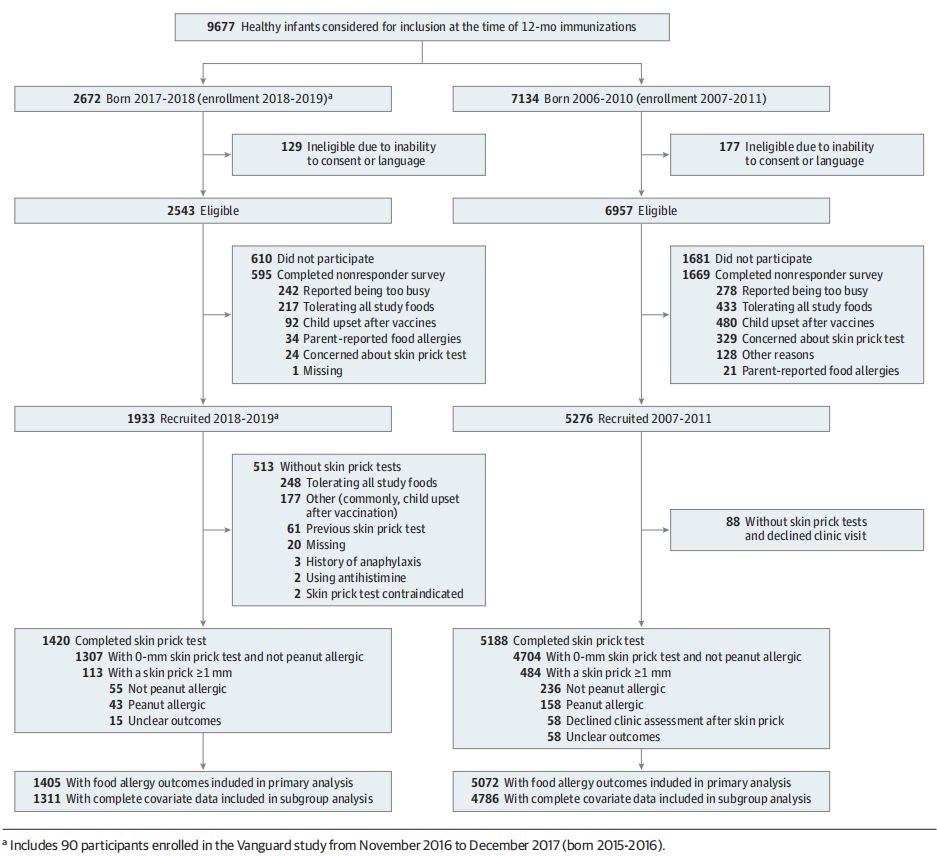

Figure 1. Flow of Participants in a Comparison of 2 Studies Evaluating Exposure and Development of Peanut Allergy in Australia

图 1. 比较 2 项评估澳大利亚花生过敏暴露和发展的研究的参与者流动情况

Researchers approached parents of 9677 infants born between 2006-2010 and 2016-2018 (Figure 1). One study recruited 1933 infants from January 2018 to December 2019 (Vanguard study: November 2016 to December 2017; n = 90). The participation rate in 2018-2019 was 76.0%. Of the 1933 participants, 1420 (73.5%) completed skin prick tests and the remainder completed the questionnaires but declined skin prick tests (26.5%) (Figure 1). Most parents reported declining a skin prick test because their child was already tolerating the study foods (n = 248 [48.3%]) or previously underwent an allergy assessment after reacting (n = 61 [11.9%]) (Figure 1). Of the 513 participants missing skin prick tests, 28 were probable or possible allergic, 369 had a history of tolerating peanut, and 116 had unknown outcomes. Overall, 1405 participants had peanut allergy outcomes, of whom 1311 had complete data for all the required variables and could be included in the analysis.

研究人员接触了 2006-2010 年至 2016-2018 年间出生的 9677 名婴儿的父母(图 1)。一项研究从 2018 年 1 月至 2019 年 12 月招募了 1933 名婴儿(先锋研究:2016 年 11 月至 2017 年 12 月;n = 90)。2018-2019年参与率为76.0%。在 1933 名参与者中,1420 人(73.5%)完成了皮肤点刺测试,其余人完成了问卷但拒绝了皮肤点刺测试(26.5%)(图 1)。大多数父母报告拒绝进行皮肤点刺测试,因为他们的孩子已经耐受研究食物(n = 248 [48.3%])或之前在反应后接受过过敏评估(n = 61 [11.9%])(图 1)。在未进行皮肤点刺测试的 513 名参与者中,28 人可能或可能过敏,369 人有耐受花生史,116 人结果未知。总体而言,1405 名参与者有花生过敏结果,其中 1311 人拥有所有必需变量的完整数据,可以纳入分析。

The participation rate from 2007-2011 was 74.0% and 2.8% of participants declined skin prick tests. In 2007-2011, a total of 5072 participants had peanut allergy outcomes, of whom 4786 participants had complete data for all the necessary variables and could be included in the analysis.

2007-2011 年的参与率为 74.0%,2.8% 的参与者拒绝进行皮肤点刺测试。2007-2011 年,共有 5072 名参与者出现花生过敏结果,其中 4786 名参与者拥有所有必要变量的完整数据,可以纳入分析。

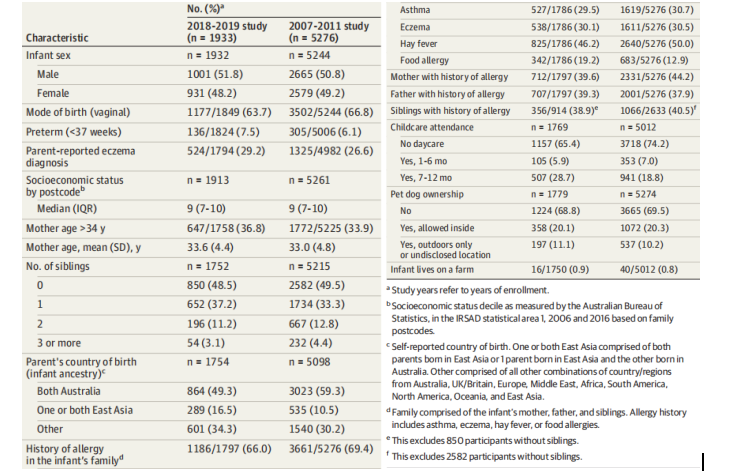

Participants were a median (IQR) age of 12.5 (12.2-13.0) months at recruitment in 2018-2019 and 12.4 (12.2-12.9) months in 2007-2011. Some differences in demographics between the 2 studies were observed (Table 1). There was a significant increase in the percentage of infants of East Asian ancestry, a previously documented risk factor for food allergy in Australia, from 10.5% to 16.5% (P < .001). The geographic origins of parents in the “other” infant ancestry category are reported in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Infants in 2018-2019 were also more likely to have parentreported eczema; however, there were only small differences after stratifying by infant ancestry (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Infants in 2018-2019 were more likely to have a family history of food allergy compared with those in 2007-2011. Participant characteristics in 2018-2019 were similar to the 2016 population demographics from the Victorian Perinatal Data Collection (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

参与者在 2018-2019 年招募时的中位 (IQR) 年龄为 12.5 (12.2-13.0) 个月,在 2007-2011 年为 12.4 (12.2-12.9) 个月。观察到 2 项研究之间的人口统计学存在一些差异(表 1)。东亚血统婴儿的百分比显着增加,这是澳大利亚先前记录的食物过敏风险因素,从 10.5% 增加到 16.5% (P < .001)。“其他”婴儿血统类别中父母的地理起源在补充材料的 eTable 2 中报告。2018-2019 年的婴儿也更有可能患有父母报告的湿疹;然而,在按婴儿血统分层后只有很小的差异(补充中的 eTable 3)。与 2007-2011 年相比,2018-2019 年的婴儿更有可能有食物过敏家族史。2018-2019 年的参与者特征与维多利亚州围产期数据收集中的 2016 年人口统计数据相似(补充中的 eTable 4)。

Table 1. Participant Demographics and History in the 2018-2019 Study and 2007-2011 Study

表 1. 2018-2019 年研究和 2007-2011 年研究中的参与者人口统计和历史

Nonparticipants in 2018-2019 were less likely to report reactions to peanut, food allergy, and introduction of peanut compared with participants who underwent the skin prick test (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Participants without skin prick tests were more likely to have introduced peanut than participants with skin prick tests (94.6% vs 86.9%), but the prevalence of parent-reported eczema and other characteristics was similar between all groups (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

与接受皮肤点刺试验的参与者相比,2018-2019 年的非参与者报告对花生、食物过敏和引入花生的反应的可能性较小(补充材料中的 eTable 5)。没有进行皮肤点刺测试的参与者比接受了皮肤点刺测试的参与者更有可能引入花生(94.6% 对 86.9%),但所有组之间父母报告的湿疹和其他特征的患病率相似(补充中的 eTable 6)。

Changes in Timing of Peanut Introduction

花生引进时机的变化

Consistent with an interim analysis of the first half of the study sample, infants in the whole 2018-2019 sample were introduced to peanut earlier than the 2007-2011 sample (85.6% vs 21.6% of participants introduced before 12 months; eTable 6 in the Supplement). Fewer infants of East Asian ancestry consumed peanut before 12 months than infants of Australian ancestry in both studies (71.8% vs 92.9% in 2018- 2019 and 16.7% vs 22.5% in 2007-2011). Peanut introduction before 12 months was less common among infants with earlyonset eczema in the 2007-2011 study, but not in the 2018- 2019 study (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

与研究样本前半部分的中期分析一致,2018-2019 年整个样本中的婴儿比 2007-2011 年样本更早地被引入花生(85.6% 对 21.6% 的参与者在 12 个月之前引入;附录中的 eTable 6)。在两项研究中,东亚血统的婴儿在 12 个月前食用花生的人数少于澳大利亚血统的婴儿(2018-2019 年为 71.8% 对 92.9%,2007-2011 年为 16.7% 对 22.5%)。在 2007-2011 年的研究中,早发性湿疹婴儿在 12 个月前引入花生的情况较少,但在 2018-2019 年的研究中则不然(附录中的 eTable 6)。

Association Between Age of Introduction and Peanut Allergy

引入年龄与花生过敏之间的关联

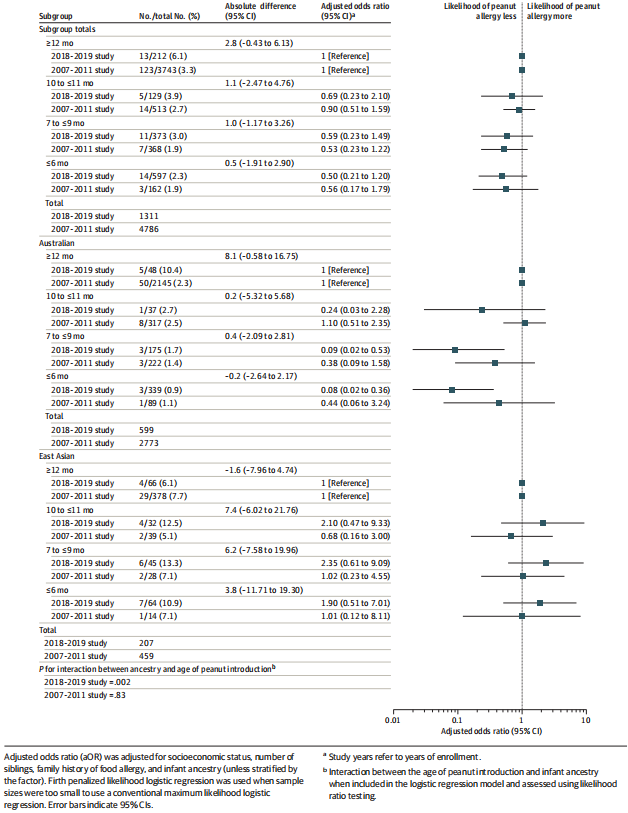

Figure 2. Association Between Age of Peanut Introduction and Peanut Allergy at 1 Year

图 2. 花生引入年龄与 1 岁时花生过敏之间的关联

There was no significant association between age of peanut introduction and peanut allergy in either of the total samples (Figure 2). There was a significant association between earlier peanut introduction and peanut allergy among infants of Australian ancestry. In the 2018-2019 study, compared with those aged 12 months or older, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.08 (95% CI, 0.02-0.36) for those aged 6 months or younger and 0.09 (95% CI, 0.02-0.53) for those aged 7 months to younger than 10 months (P value for interaction in the 2018- 2019 study between ancestry and earlier peanut introduction = .002; eTable 1 in the Supplement). There was no significant association between earlier peanut introduction and peanut allergy among infants of East Asian ancestry. Results were similar when early-onset eczema was added into the model as a sensitivity analysis (eFigure 3 in the Supplement) and in unadjusted results (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

在任一总样本中,花生引入的年龄与花生过敏之间没有显着关联(图 2)。在澳大利亚血统的婴儿中,早期引入花生与花生过敏之间存在显着关联。在 2018-2019 年的研究中,与 12 个月或以上的人相比,6 个月及以下的人调整优势比为 0.08(95% CI,0.02-0.36)和 0.09(95% CI,0.02-0.53) 那些年龄在 7 个月至小于 10 个月的人(2018-2019 年研究中祖先与早期花生引入之间相互作用的 P 值 = .002;补充材料中的 eTable 1)。在东亚血统的婴儿中,早期引入花生与花生过敏之间没有显着关联。将早发性湿疹作为敏感性分析(附录中的 e图 3)和未调整的结果(附录中的 e表 7)添加到模型中时,结果相似。

Prevalence of Peanut Allergy in 2018-2019 vs 2007-2011

2018-2019 年与 2007-2011 年花生过敏的患病率

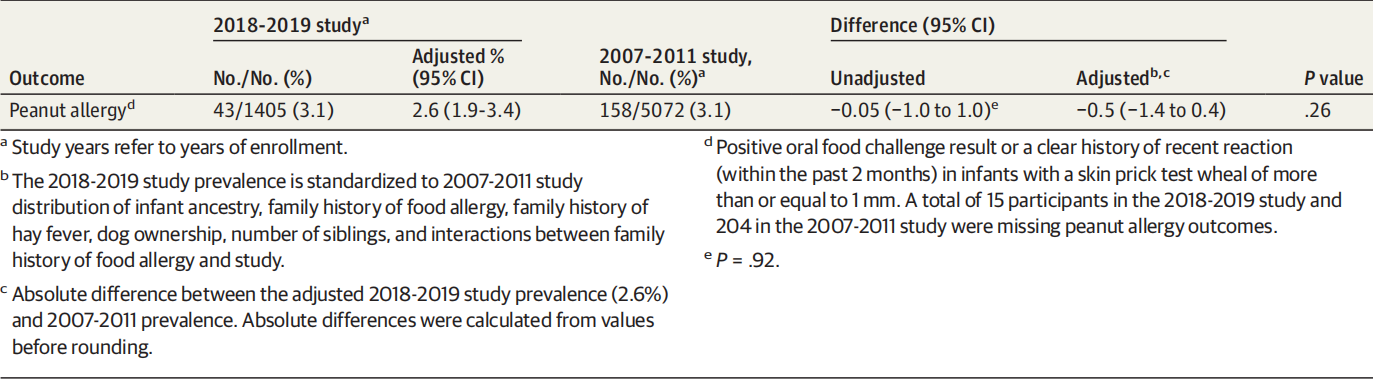

The observed prevalence of peanut allergy in 2018-2019 was 3.1% ([95% CI, 2.3%-4.1%]; 43 of 1405 infants; Table 2). This estimate was similar after using inverse probability weighting to correct for potential selection bias due to incomplete participation (3.0% [95% CI, 2.1%-4.1%]).

2018-2019 年观察到的花生过敏患病率为 3.1%([95% CI,2.3%-4.1%];1405 名婴儿中有 43 名;表 2)。在使用逆概率加权来纠正由于不完全参与导致的潜在选择偏差后,这一估计值相似(3.0% [95% CI,2.1%-4.1%])。

Table 2. Prevalence of Peanut Allergy in 2018-2019 vs 2007-2011 in Infants in Australia

表 2. 2018-2019 年与 2007-2011 年澳大利亚婴儿花生过敏的患病率

After standardizing to the 2007-2011 baseline distribution for the select factors, the adjusted prevalence of peanut allergy in 2018-2019 was 2.6% (95% CI, 1.9-3.4) (Table 2). There was no significant decrease in peanut allergy compared with the observed prevalence in 2007-2011 (158 of 5072 [3.1% (95% CI, 2.7%-3.6%)]; P = .24).

在将选定因素标准化为 2007-2011 年基线分布后,2018-2019 年花生过敏的调整后患病率为 2.6%(95% CI,1.9-3.4)(表 2)。与 2007-2011 年观察到的患病率相比,花生过敏没有显着下降(5072 人中有 158 人 [3.1% (95% CI, 2.7%-3.6%)];P = .24)。

Peanut allergy prevalence was then further stratified by the risk factors infant ancestry and early-onset eczema. There was no significant decrease in standardized peanut allergy prevalence among either East Asian infants or among Australian infants (eTable 8 in the Supplement). There was also no significant interaction with infant ancestry (P = .07).

然后根据婴儿血统和早发性湿疹的危险因素进一步对花生过敏患病率进行分层。东亚婴儿或澳大利亚婴儿的标准化花生过敏患病率没有显着降低(补充资料中的表 8)。与婴儿血统也没有显着的相互作用(P = .07)。

Among infants with early-onset eczema, 20 of 165 in 2018-2019 and 73 of 516 in 2007-2011 had peanut allergies. The standardized peanut allergy prevalence among children with early-onset eczema in 2018-2019 was 9.3% (95% CI, 5.2%-13.9%), compared with 14.1% (95% CI, 11.4%-17.4%) in 2007-2011 (difference, −4.9% [95% CI, −10.4% to 0.4%]; P = .08; eTable 9 in the Supplement). There was no significant interaction with early-onset eczema (P = .21).

在患有早发性湿疹的婴儿中,2018-2019 年 165 名婴儿中有 20 名患有花生过敏症,2007-2011 年 516 名婴儿中有 73 名患有花生过敏症。2018-2019年早发型湿疹患儿标准化花生过敏患病率为9.3%(95% CI,5.2%-13.9%),而2007-2011年为14.1%(95% CI,11.4%-17.4%)(差异,-4.9% [95% CI,-10.4% 至 0.4%];P = .08;补充材料中的 eTable 9)。与早发性湿疹没有显着的相互作用(P = .21)。

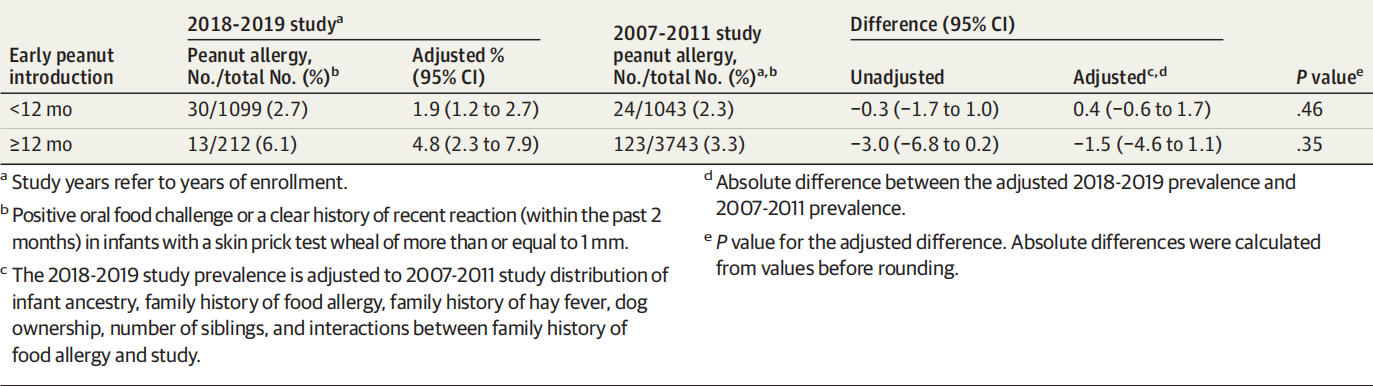

Table 3. Prevalence of Peanut Allergy by Age of Peanut Introduction

表 3. 按花生引入年龄划分的花生过敏患病率

The unadjusted prevalence of peanut allergy in 2018- 2019 was 2.7% (95% CI, 1.9%-3.9%) among infants with early peanut introduction and 6.1% (95% CI, 3.6%-10.3%) among infants without early peanut introduction (Table 3). Within strata of age of peanut introduction categories, the standardized prevalences of peanut allergy within every category from 2007- 2011 to 2018-2019 were not significantly different (Table 3 and eTable 10 in the Supplement). A sensitivity analysis adding early-onset eczema to the models gave similar results (eTable 11 in the Supplement).

2018-2019 年花生过敏未调整患病率在早期引入花生的婴儿中为 2.7%(95% CI,1.9%-3.9%),在未早期引入花生的婴儿中为 6.1%(95% CI,3.6%-10.3%)(表3)。在花生引入类别的年龄层内,2007-2011 年至 2018-2019 年每个类别中花生过敏的标准化患病率没有显着差异(补充材料中的表 3 和 eTable 10)。将早发性湿疹添加到模型中的敏感性分析给出了类似的结果(补充中的 eTable 11)。

Discussion

讨论

The introduction of a guideline recommending early peanut introduction in Australia was not associated with a statistically significant lower or higher prevalence of peanut allergy across the population in analyses of 2 population-based samples of infants aged 1 year.

在对 2 个基于人群的 1 岁婴儿样本的分析中,建议在澳大利亚早期引入花生的指南的引入与人群中花生过敏的统计学显着性较低或较高患病率无关。

This study found an increase in infants of East Asian ancestry (parents born in East Asia), concordant with population data from the 2016 Victorian Perinatal Data Collection, compared with the 2007-2011 study. This increase was relevant because a previous study showed higher likelihood of peanut allergy (adjusted odds ratio, 3.3 [95% CI, 2.5-4.5]) among infants born in Australia to East Asian parents. Despite the higher prevalence of this risk factor in the 2018- 2019 study, peanut allergy prevalence did not increase in 2018- 2019. It is possible thatwidespread early introduction of peanut products in infancy blunted the rise in peanut allergy that could have otherwise occurred.

与 2007-2011 年的研究相比,这项研究发现,与 2007-2011 年的研究相比,2016 年维多利亚围产期数据收集的人口数据与东亚血统婴儿(父母出生在东亚)的数量有所增加。这种增加是相关的,因为之前的一项研究表明,在澳大利亚出生的婴儿与东亚父母相比,花生过敏的可能性更高(调整优势比,3.3 [95% CI,2.5-4.5])。尽管在 2018-2019 年的研究中这种风险因素的患病率较高,但花生过敏的患病率在 2018-2019 年并没有增加。婴儿期广泛早期引入花生产品可能会减缓原本可能发生的花生过敏的上升。

Earlier peanut introduction was significantly associated with lower risk of peanut allergy among infants of Australianborn parents, but not among infants of East Asian ancestry, in the 2018-2019 cohort. These results were contrary to findings from the LEAP randomized clinical trial in UK infants, which showed earlier peanut introduction prevented peanut allergy among those of the “Indian subcontinent” (n = 24) but not in “Asian” infants (n = 8) from “China, Middle East, and other.” Different introduction patterns may have contributed to the findings. Infants of East Asian ancestry in this study were introduced to peanut later, which may have attenuated the association with early peanut introduction in East Asian infants. There is also some evidence from other studies conducted in Asia that the timing of introduction of allergenic foods may be less important among infants of Asian ancestry. More trials are needed to look into the optimal frequency and quantity of peanut consumption to prevent peanut allergy, because the study design and data structure in this study were not optimal to explore this question.

在 2018-2019 年队列中,早期引入花生与澳大利亚出生的婴儿的花生过敏风险降低显着相关,但与东亚血统的婴儿无关。这些结果与在英国婴儿中进行的 LEAP 随机临床试验的结果相反,该试验表明,早期引入花生可以预防“印度次大陆”(n = 24)的花生过敏,但不能预防来自“亚洲”婴儿(n = 8)的花生过敏。“中国、中东等。”不同的引入模式可能促成了这些发现。本研究中东亚血统的婴儿后来被引入花生,这可能减弱了东亚婴儿早期花生引入的关联。在亚洲进行的其他研究也有一些证据表明,在亚洲血统的婴儿中引入过敏性食物的时间可能不太重要。需要更多的试验来研究花生食用的最佳频率和数量以预防花生过敏,因为本研究中的研究设计和数据结构并不是探索这个问题的最佳选择。

The evidence that early introduction of peanut could prevent peanut allergy was largely derived from a UK trial conducted in infants with early-onset eczema, who were therefore at high-risk of developing peanut allergy. A second trial in infants recruited from the general population did not show a significant decrease in peanut allergy in the early introduction group in the intention-to-treat analysis. Similarly, the prevalence of peanut allergy in this study did not decrease significantly in the general population over time.

早期引入花生可以预防花生过敏的证据主要来自英国一项针对患有早发性湿疹的婴儿进行的试验,这些婴儿因此处于发生花生过敏的高风险中。在意向治疗分析中,从普通人群中招募的婴儿的第二项试验未显示早期引入组的花生过敏显着降低。同样,本研究中花生过敏的患病率并没有随着时间的推移在普通人群中显着下降。

The high prevalence of peanut allergy in Melbourne, Australia, despite early peanut introduction, suggests an important contribution of other early life environmental factors. An increase in less-researched environmental risk factors, potentially interacting with genetic susceptibility, could have masked the protective association with earlier peanut introduction. Maternal gut microbiome, vitamin D deficiency, and early life microbial exposure are 3 potential food allergy risk factors that were not measured in this study. Early introduction of peanut alone is also unlikely to prevent other food allergies and therefore may not change overall food allergy prevalence. Overall, the findings of this study were consistent with early peanut introduction as an important preventative strategy; however, early peanut introduction alone was not likely to be sufficient to eliminate peanut allergy.

尽管早期引入花生,但澳大利亚墨尔本的花生过敏率很高,这表明其他早期生活环境因素的重要贡献。研究较少的环境风险因素的增加,可能与遗传易感性相互作用,可能掩盖了与早期花生引入的保护性关联。母体肠道微生物群、维生素 D 缺乏和生命早期微生物暴露是本研究未测量的 3 个潜在食物过敏风险因素。单独早期引入花生也不太可能预防其他食物过敏,因此可能不会改变整体食物过敏患病率。总体而言,这项研究的结果与早期引入花生作为一种重要的预防策略是一致的。然而,仅早期引入花生可能不足以消除花生过敏。

This study has several strengths. First, these large population-based studies were specifically designed to answer this research question and used objective, challenge-proven peanut allergy outcomes. They allowed a comparison of peanut allergy prevalence before and after the introduction of new infant feeding guidelines. Second, both studies recruited participants from the same geographical location using the same recruitment methods and sampling frame. Third, the demographic characteristics of both studies were broadly representative of the general population. A large range of food allergy risk factors and temporal changes in population demographics were measured and adjusted for over time using inverse probability weighting and standardization, thereby reducing bias.

这项研究有几个优点。首先,这些基于人群的大型研究是专门为回答这个研究问题而设计的,并使用了客观的、经过挑战证明的花生过敏结果。他们允许比较引入新婴儿喂养指南前后的花生过敏患病率。其次,两项研究都使用相同的招募方法和抽样框架从同一地理位置招募参与者。第三,两项研究的人口学特征广泛代表了一般人群。随着时间的推移,使用逆概率加权和标准化来测量和调整大量食物过敏风险因素和人口统计数据的时间变化,从而减少偏差。

Limitations

限制

This study has several limitations. First, there was a lower rate of participation in skin prick tests in 2018-2019 compared with 2007-2011. Families mainly declined a skin prick test when their infants were already eating and tolerating peanut or already seeing a physician after earlier allergic reactions after eating peanut. Second, there were minor differences in peanut allergy risk factors between those with and without skin prick tests as well as nonparticipants; however, the prevalence estimates did not substantially change when weighting to correct for potential bias due to partial participation. Moreover, the prevalence of “probable/possible peanut allergy” among partial participants was similar to peanut allergy among complete participants, suggesting that the lower rate of skin prick tests in 2018-2019 vs 2007-2011 is not likely to explain the small difference in peanut allergy between the studies. Third, because data were collected retrospectively at 12 months, any nondifferential misclassification of age at first peanut introduction (parents misremembering age) would bias the association results toward the null, rather than explain the observed association. Furthermore, cross-sectional data collection avoids possible changes in participant feeding behavior caused by the awareness of being studied.

这项研究有几个局限性。首先,与 2007-2011 年相比,2018-2019 年皮肤点刺测试的参与率较低。当他们的婴儿已经在吃花生并耐受花生或在吃花生后出现早期过敏反应后已经去看医生时,家庭主要拒绝进行皮肤点刺试验。其次,进行和未进行皮肤点刺试验的人与非参与者之间的花生过敏危险因素存在细微差异;然而,当加权以纠正由于部分参与导致的潜在偏差时,患病率估计值没有显着变化。此外,部分参与者中“可能/可能的花生过敏”的患病率与完整参与者中的花生过敏相似,这表明 2018-2019 年与 2007-2011 年相比,皮肤点刺试验的较低比例不太可能解释两者之间的微小差异。研究之间的花生过敏。第三,由于数据是在 12 个月时回顾性收集的,因此首次引入花生时对年龄的任何非差异错误分类(父母误记年龄)都会使关联结果偏向于零,而不是解释观察到的关联。此外,横断面数据收集避免了参与者进食行为因被研究意识而可能发生的变化。

Conclusion

结论

In this cross-sectional analyses, introduction of a guideline recommending early peanut introduction in Australia was not associated with a statistically significant lower or higher prevalence in peanut allergy across the population.

在这项横断面分析中,在澳大利亚引入推荐早期引入花生的指南与人群中花生过敏患病率显着降低或升高无关。